|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| LitNet is ’n onafhanklike joernaal op die Internet, en word as gesamentlike onderneming deur Ligitprops 3042 BK en Media24 bedryf. |

|

|

|

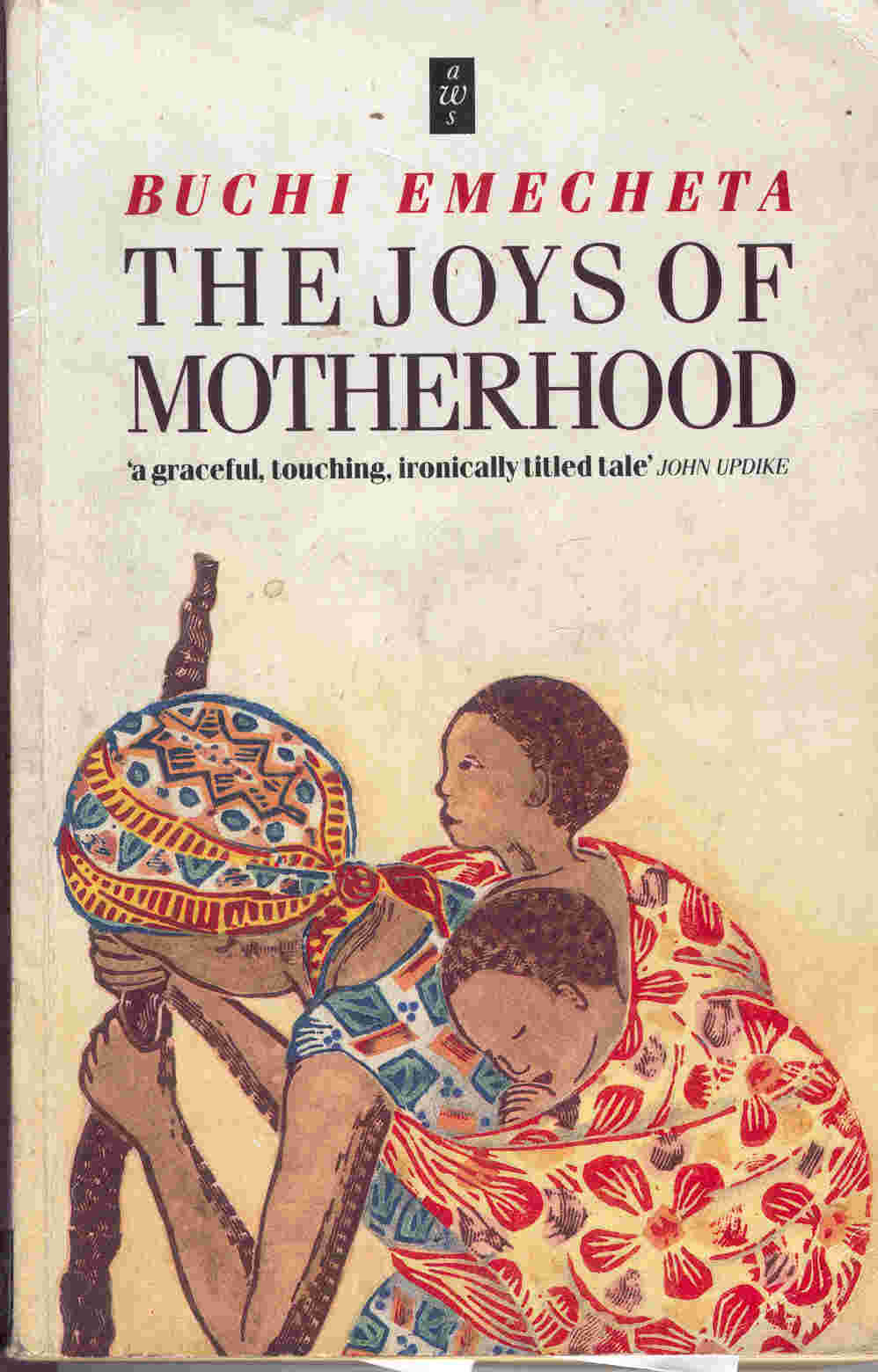

The Joys of Motherhood

Buchi Emecheta

Among African writers, the Nigerian author Buchi Emecheta is a well-established

figure. None of her works has equalled The Joys of Motherhood in its

well-deserved and enduring fame, however. It can be considered one of the classics

of the African novel tradition. Some readers even see it as a sort of “counterpart”

to the most famous of all African English novels, Achebe’s Things Fall

Apart, in that it depicts the beginnings of the colonisation as this incursion

affected the Igbo people of Eastern Nigeria — but unlike Achebe’s

somewhat male-centred view of Igbo life, Emecheta provides a strongly female

(though no less complex) perspective on the same culture.

The novel has one of the most memorable, striking opening scenes amongst the

many I know. It depicts Nnu Ego, the main protagonist (a young mother living

with her husband, a washerman to a white couple, in the huge city of Lagos)

at the moment that she discovers that her long-awaited baby boy, her first child,

has suddenly and inexplicably died in his sleep. The horror of it is so overwhelming

that she reels back and then rushes away in a state of dementia, intent only

on casting herself from the main city bridge to drown there. But even in huge,

polyglot Lagos, someone in the early morning crowd — a fellow-Igbo —

recognises and restrains her, and she is pacified and returned to her home.

Of course the reader has by now recognised how profoundly sardonic the name

of this novel is, a realisation only intensified as (in the following chapters)

one is taken into the background of Nnu Ego’s situation.

Her mother’s short life, that ended soon after Nnu Ego’s birth, is

vividly told. The chapter called “The Mother’s Mother” begins

by describing Nnu Ego’s father, however, a man who was one of the great

lords of his village community. Already a mature and wealthy man with numerous

wives, Agbadi had only one woman in his heart — Ona, the “priceless

jewel” or apple of the eye of his oldest friend, a delightful, spirited

woman many years younger than himself. Emecheta tells this preamble story with

consummate skill for, although it is an endearingly “romantic” tale,

it is shot through with her sardonic recognition that the relationship is nevertheless

profoundly askew in its power relations. Ona — who seems able (in the old

expression) to twist both her mature lover and her father around her little

finger — is (nevertheless) caught in a sort of cross-fire of possessive

demands upon her from both these men. On her death-bed (she dies when her and

Agbadi’s second baby is still-born) she — poignantly- asks the heart-broken

Agbadi to “allow [their daughter, Nnu Ego] to have a life of her own, a

husband if she wants one. Allow her to be a woman” (28).

Nnu Ego is a considerably more conventional person than her mother was. Always

eager to please her widowed father, she marries the glamorous young husband

whom he chooses for her with great hopes. It all soon turns sour, however, when

she is unable to conceive, and is supplanted by a fertile young second wife

and ignominiously assaulted and rejected by her husband. Well-meaning as he

is, Agbadi decides to soothe his daughter’s wounded feelings by marrying

her off a second time — as far away as possible from their area (where

she might run into her first husband). The second husband, unfortunately, is

even more unsuitable: fat and unattractive, but impenetrably complacent in his

maleness. Nnu Ego, at first full of disdain towards Nnaife, reluctantly begins

to accept him when she falls pregnant. For this short period, and here only,

Nnu Ego experiences something of the joyousness that the title seems to invoke

— but then fate snatches her child from her.

Without the novelist articulating the point in so many words, this loss produces

a neurosis in Nnu Ego that she never overcomes. It enslaves her to ensure the

survival of her numerous subsequent children (especially her sons) at whatever

cost to her own health or quality of life this may require. She withdraws into

motherhood, no longer trading or visiting, and the family falls into real poverty

when Nnaife’s British employers leave. He is forced to accept a job that

takes him out of the country and Nnu Ego is left to fend for herself and her

children. The terrible, terrifying life of the urban poor descends upon them.

Nnu Ego gets a second boy and life gets even harder.

Suddenly, Nnaife returns. At least he has made some money, and for a brief while

they are quite prosperous. Then comes the news that his elder bother has died,

and, according to Igbo custom, Nnaife has to “inherit” one of the

widowed wives — who arrives almost immediately with her daughter, confident

of being accepted. But maintaining the old customs in the urban environment

is hard, almost unbearable for Nnu Ego. Gallingly, she has to lie and witness

her husband and his second wife’s sexual enthusiasm. And in so cash-strapped

a household, rivalries and tensions constantly intensify.

Nnaife’s attitude towards Nnu Ego hardens — he is especially disdainful

towards their twin daughters as “mere” girls.

Suddenly Nnaife is forcefully conscripted into the army, for World War II has

broken out and Britain needs soldiers. The two wives are left to fend for themselves

and the houseful of children. While Nnu Ego again subsides into destitution,

her co-wife becomes a prosperous trader. But because she has no male child and

feels unvalued, the younger woman decides to leave the household, even indulging

in prostitution. Nnu Ego wraps “respectability” around her like a

cloak. In the narrator’s ironic description, Nnu Ego wishes her departing

co-wife well “as she crawled further into the urine-stained mats on her

bug-ridden bed” (169).

The intractable patriarchal perspective that was drummed into Nnu Ego keeps

taking its toll on her. Her boys must be educated; her daughters must help her

to earn. When Nnaife at last returns he does little to lighten her load. His

mind is set on “compensation” for the absconded co-wife. This time

he chooses a sixteen-year-old girl whose bride price swallows up much of his

army pay. Nnu Ego’s outcry against such foolishness is to no avail. “Her

love and duty for her children were like her chain of slavery” (186). The

sons all do well and become highly educated, but further rifts develop in the

family. Given his flabby nature it is predictable that Nnaife blames his quarrels

with his children on Nnu Ego.

Most devastating to Nnu Ego is his venom directed against her when one of their

twin daughters runs away to marry against his wishes. When he is jailed for

his violent attack on the family his daughter went to, the rift between him

and Nnu Ego is final. In her later years (she is in fact only middle-aged),

Nnu Ego returns to the village of her youth, but she is broken in body and spirit.

Although some of her children lovingly support her, she feels abandoned and

betrayed. Her death is a lonely one. Her eldest son gives her the “most

costly second burial” the village has ever seen. But it is too late. All

her bright vitality drained away much too soon.

Perhaps an account of this kind makes the novel seem a mere tale of woe. What

is remarkable, though, is how intelligent a book Emecheta has written. The writing

is beautifully vivid and the detail well observed. Moreover, the author’s

ability to hold one’s attention is superbly skilful. There is always something

of a distance, something of a warning in the narrator’s tone, and surprisingly,

a sort of black humour. For the main character Nnu Ego is, for all the profound

empathy with which her tale is told, a woman who knuckles under, who is to some

extent at least complicit in the web of patriarchal values that enmeshes her.

Her story is tragic — and at the same time ironically cautionary. Emecheta’s

exposure of the woes of modernisation’s uncomfortable incorporation of

ancient hierarchies is one that no reader will easily forget.

to the top

|